1. Introduction to this Guide

So, you want to know how to improve your preliminary and HSC economics essay writing? Look no further! In this guide, I’ll be covering key tips to help YOU smash the structure, amaze with your analysis, conquer the contemporary, and ultimately master the mystery of maximising your marks.

My name is Cory Aitchison, currently one of the Economics tutors at Project Academy. I completed the HSC in 2018, achieving a 99.95 ATAR as well as two state ranks — 6th in economics and 12th in chemistry. Graduating from Knox Grammar School, I also topped my grade in economics and was awarded Dux of the School for STEM. Believe it or not, at the beginning of Year 11 I initially struggled with economics due to the transition in conceptual thinking required in approaching economic assessments in comparison to my other subjects such as English. However, through Year 11 and Year 12, I built up key tips and strategies — that I’ll be sharing with you in this guide — to help me not only consistently achieve top marks in my internal assessments, but to ultimately go on to achieve the results I did in the HSC.

2. The Correct Way to Write

First off, you need to understand something: HSC economics essays are NOT english essays! They aren’t scientific discussions, nor geography reports, nor historical recounts. They’re unique and often quite different from other essays that you might’ve done previously in high school. The style of writing and approach to answering questions can be confusing at first, but follow these tips and you’ll be ready in no time:

Phrasing should be understandable and concise

Unlike some subjects where sophisticated phrasing is beneficial to getting marks, HSC economics essays should emphasise getting your point across with clarity. This means don’t run your sentences on for too long, be aware of any superfluous words, and make sure you actually understand yourself what you’re trying to say in a sentence.

For example:

GOOD: “An increase in interest rates should lead to decreased economic growth.”

NOT GOOD: “As a result of a rise or increase in interest rate levels from their previous values, the general state of economic activity in the domestic economy may begin to decrease and subsequently indicate the resultant situation of a decrease in economic growth.”

“Understandable” does not mean slang or lacking in terminology

Just because you want to get a point across, doesn’t mean you should resort to slang. In fact, using economic terminology is a strong way to boost your standing in the eyes of the marker — if you use it correctly! Always make sure you use full sentences, proper English grammar, and try and incorporate correct economic terms where possible.

GOOD: “This was a detrimental outcome for the economy.”

NOT GOOD: “This was a pretty bad outcome for the economy.”

GOOD: “The Australian Dollar depreciated.”

NOT GOOD: “The Australian Dollar decreased in value.”

Analysis should be done using low modality

Modality just refers to the confidence of your language — saying something “will” happen is strong modality, whereas saying something “might” happen is considered low modality. Since a large portion of economics is about applying theory, we have to make sure that we are aware that we are doing just that — talking about the theoretical, and so we can’t say for sure that anything will happen as predicted.

Some useful words include:

May, Might, Should, Could, Can theoretically

Don’t use words like:

Must, Will, Has to, Always

3. How to use Statistics

“What’s most important is that this contemporary is used to bring meaning or context to your argument…”

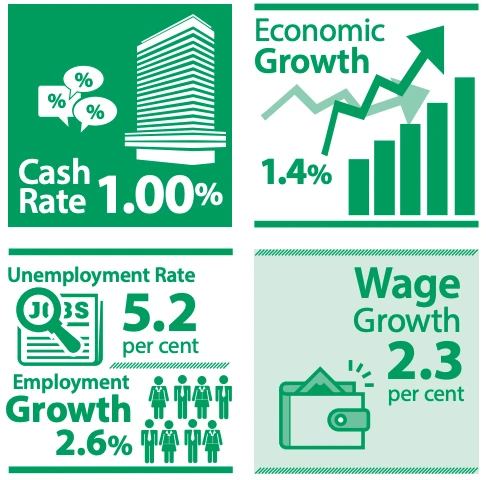

Using contemporary (statistics) can often seem straightforward at first, but using it effectively is usually harder than it looks. Contemporary generally refers to applying real-world facts to your analysis to help strengthen (or weaken) the theoretical arguments. This can include many different statistics or pieces of information, including:

- Historic economic indicators, such as GDP, inflation, GINI coefficients, exchange rates, or unemployment rates

- Trends or economic goals, such as long-term GDP growth rates, or the stability band for inflation

- Names of economic policies, such as examples of fiscal or microeconomic policies

- Specifics of economic policies, such as the amount spent on infrastructure in 2017

Whatever statistics you deem relevant to include in your essay, what’s most important is that this contemporary is used to bring meaning or context to your argument — just throwing around random numbers to show off your memorisation skills won’t impress the marker, and in fact might appear as if you were making them up on the spot. Rather, your use of contemporary should actively improve your analysis.

For example:

GOOD: “Following a period of growth consistently below the long-term trend-line of 3%, the depreciation of the AUD to 0.71USD in 2017 preceded an increase in economic growth to a 10-year high of 3.4% in 2018.”

NOT GOOD: “Economic growth increased by 1 percentage point in 2017 to 2018”

NOT GOOD: “GDP was $1.32403 trillion in 2017”

GOOD: “The 2017 Budget’s Infrastructure Plan injected $42 billion into the economy — up 30% from 2016’s $31 billion, and 20% higher than the inflation-adjusted long-term expenditure.”

NOT GOOD: “The 2017 Budget’s Infrastructure Plan injected $42 billion into the economy”

That in mind, don’t think that these statistics have to be overly specific. As long as the general ideas gets across, it’s fine. You don’t need to say “$1,505,120” — just “$1.5 million” will suffice.

Ask yourself: if I get rid of the contemporary from my paragraphs, does the essay still have enough content?

Further, don’t get roped into the “contemporary trap” — where you fall into the mindset that “if I memorise all these statistics, my essay will get good marks”. Including numbers and contemporary at the expense of having a robust theoretical explanation and analysis will definitely be detrimental in getting you top marks. Particularly in trial exams and the HSC when you’ve got all these numbers floating in your head, it can be tempting to try and include as many as you can (often just because you can!). To avoid this, always try and focus your arguments on analysis and syllabus content first, contemporary second. Ask yourself: if I get rid of the contemporary from my paragraph, does the essay still have enough content?

4. Must Have Insightful “However”s

If you really want to extend your analysis and show the marker that you know your stuff, including insightful “however”s is a strong way to do it. What I mean by this is that for each of your paragraphs, try and include a counterpoint that highlights the flexible nature of economic theory. There are broadly two kinds of “however”s:

Theoretical “However”s

These are counterpoints that are based on theory — often there will be theoretical limitations for many of the concepts you come across in economics. It’s always important to include these limitations as it reinforces your knowledge of the actual content of economics.

For example:

“Although the Budget and fiscal policy can be effective at stimulating economic growth, it is also restricted by the “implementation time lag” limitation since it is only introduced annually.”

Contemporary “However”s

These are counterpoints that are based on contemporary — highlighting how although something should happen theoretically, this isn’t usually what is observed in reality. This can be particularly powerful in that it combines your knowledge of theory with your analysis of contemporary.

For example:

“Despite the expansionary stance that the RBA adopted in 2012–2016 for monetary policy, Australia’s annual GDP growth rate has remained below the trend rate of 3% — against the theoretical expectations. This could be attributed to factors such as …”

5. How to Interpret the Question

When you first look at a question, before you even put pen to paper, you need to come up with a plan of attack — how can you ensure that you answer the question correctly, and give the markers what they want? There are three main points to look for when interpreting essay questions:

Knowing your verbs

As you may (or may not) know, NESA has a bank of words that they like to pull from when writing questions, and these words impact how they want their question answered. These verbs should help steer your analysis onto the right path. For example:

Explain: “Relate causes and effects”

To answer these questions, you have to demonstrate a thorough understanding of how theory and events impact each other and the economy. This verb particularly emphasises the idea of a process — you need to be able to make clear links as to how each step leads to the next, rather than just jumping to the outcomes.

Analyse: “Draw out and relate implications”

These questions usually wants you to investigate the connections between different aspects of economic theory. Generally this involves showing a holistic understanding of how different areas (such as micro- and macroeconomic policies) come together to make a cohesive impact on the economy. It usually helps to think back to the syllabus and how the points are introduced when figuring out which ideas to link together.

Assess/Evaluate: “Make a judgement based on value/a criteria”

These require you to not only critically analyse a topic but also come to a conclusion given the arguments you provided. This type of question usually gets you to make a judgement of the effectiveness of some economic theory — such as the ability for economic policies to achieve their goals. Make sure you actually include this judgement in your answer — for example, say things like “strong impact”, “highly influential”, “extremely detrimental”.

Discuss: “Provide points for and/or against”

Similar to assess, discuss wants you to provide arguments towards and against a particular topic. Although it doesn’t require a specific judgement to be made, it does place greater emphasis on showing a well-rounded approach to the argument — providing relatively equal weightings towards both the positive and negative sides of the discussion.

Linking to the syllabus

When trying to understand what the question wants from you, I found the best way to approach it is to consider what points in the syllabus it is referring to (To do this, you need to have a solid understanding of the syllabus in the first place). Once you’ve located it, try drawing upon other topics in the vicinity of that dot point to help you answer the question.

For example, if the question mentions “trends in Australia’s trade and financial flows”, then you know from the syllabus that you probably need to talk about value, composition and direction in order to get high marks. Further, it may also be worth it to bring in ideas from the Balance of Payments, as this is the next dot point along in the syllabus.

Digging into the source

For essay questions that provide a source for you to include in your answer, this is another goldmine from which you can discern what the marker really wants. If the source mentions microeconomic policy, it probably wasn’t on accident! Even if it may not be obvious how to link that to the question immediately, try and draw upon your knowledge and implications and see if there’s a different angle that you might be missing.

6. Putting it All together — Structuring your essay

My essays usually consisted of four main parts: an introduction, a background paragraph, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Introduction

Your introduction should not be long. I rarely wrote an introduction longer than three sentences.

First sentence: Answer the question (thesis)

Try and answer the question, while including the main key words of the question in your answer. Don’t directly restate it — instead, try and add meaning to it in a way that represents what you’re trying to get across in your essay.

For example: if the question was “Assess the impact of microeconomic policy in improving economic growth in Australia”, my first sentence might be “Microeconomic policy has had a significant impact in increasing aggregate supply and thus long-term economic growth in Australia since the 1960s”.

Next sentences: Introduce your arguments/paragraphs

In this part, it’s fine to almost list your paragraphs — there’s no need to do a whole sentence explaining each. That’s what the paragraphs themselves are for.

For example: using the same question as above, my next sentence might be “Although trade liberalisation may have been detrimental for short-term growth in manufacturing, policies such as competition policy and wage decentralisation have been highly effective in fostering economic growth in Australia”.

Background Paragraph

The aim of a background paragraph is threefold: to get across the main theory that underpins your argument; to establish the economic context for your argument; and to show the marker that you “know your stuff”.

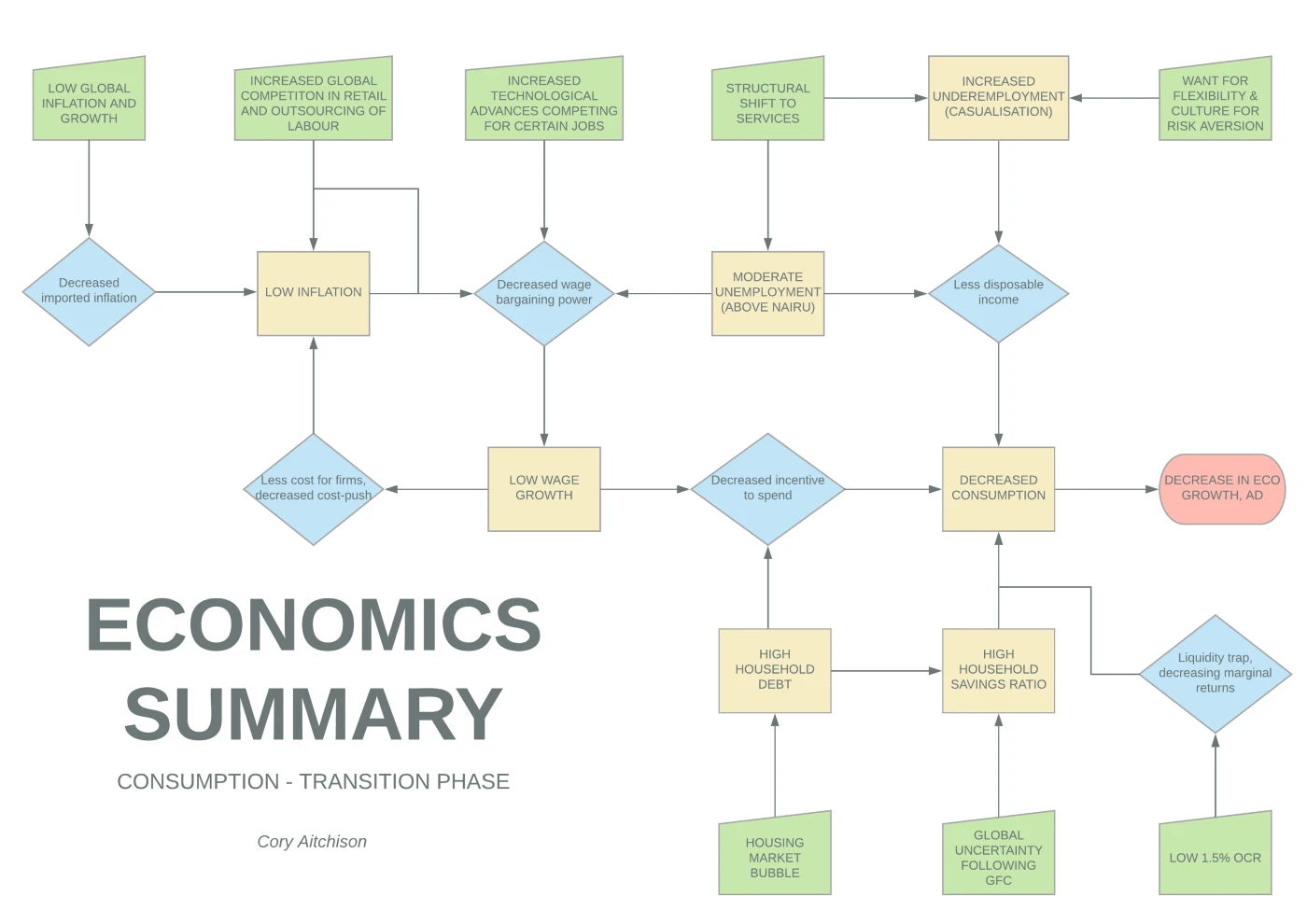

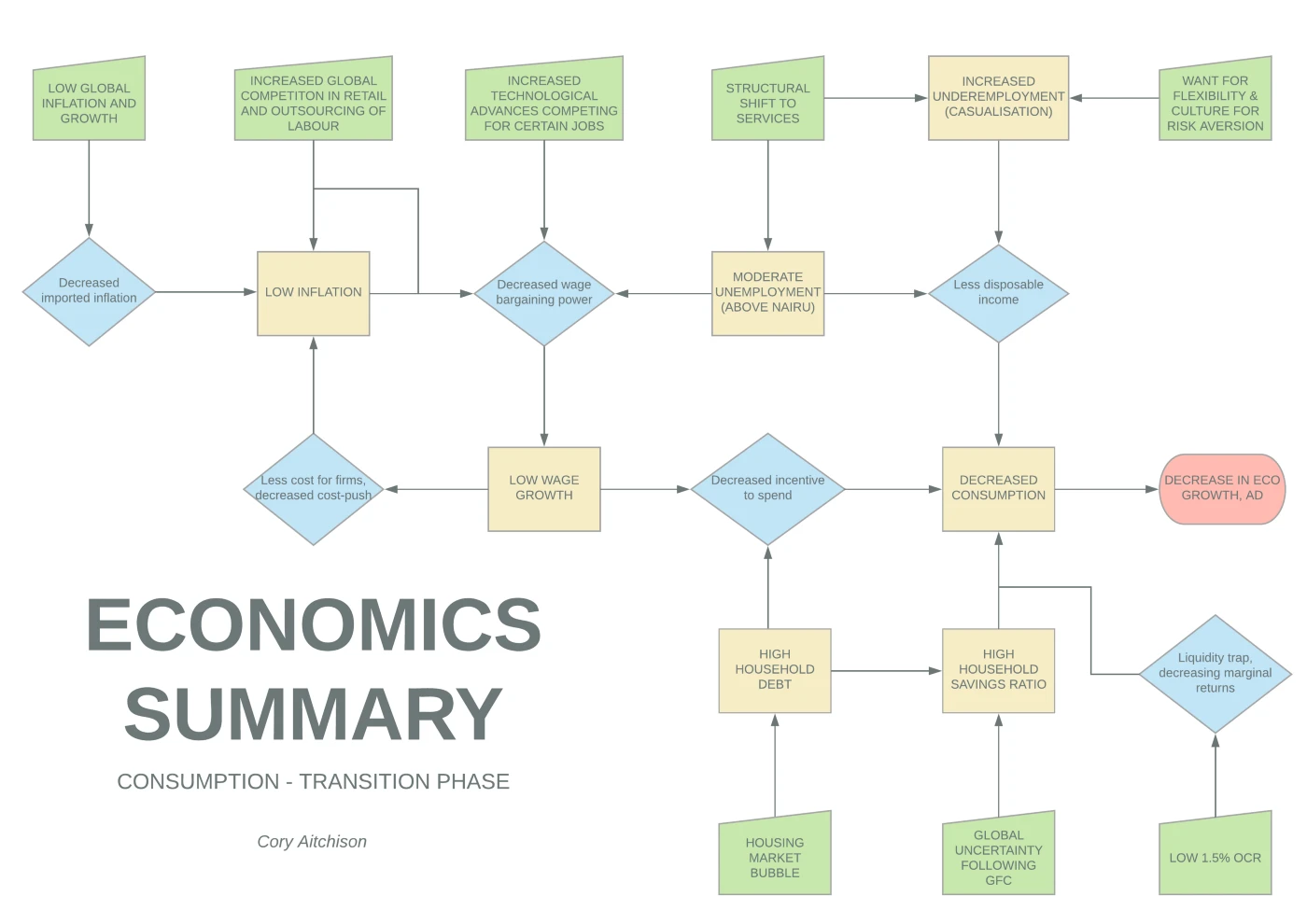

For example, if the essay was on monetary policy, you may want to describe the process of Domestic Market Operations (how the reserve bank changes the cash rate) in your background paragraph, so that you don’t need to mention it each time you bring up changing stances. Further, it may be good to showcase the current economic climate — such as GDP growth rate and inflation — to give context to your analysis in your essay.

Some ideas for what to include in this paragraph include:

- Key theory such as DMOs or the rationale for macroeconomic policies

- Economic indicators that provide context to the time period that you’re working in, such as growth rates, inflation, unemployment rates, exchange rates, cash rates, etc.

- A brief description of the recent Budget (if talking about fiscal policy), including the stance and outcome

Bear in mind that this paragraph shouldn’t be too long — it isn’t the focus of your essay! Instead, aim for around 100–150 words at most. At this point in your essay, it may also be good to include a graph (more on this later).

Body Paragraphs

There’s no set rule for how many body paragraphs to include in your essay — I generally aim for at least 4, but there’s no real limit to how many you can (or should) write! Unlike english essays, it’s totally acceptable to just split a paragraph in two if you feel like the idea is too large to be written in one paragraph (as long as each paragraph makes sense on its own).

When writing a paragraph, I usually follow this structure:

Topic sentence

This is where you answer the question, and outline your argument or idea for this paragraph. If you are doing a discuss/assess/evaluate essay, try and make your judgement or side obvious. For example: “Trade liberalisation has been detrimental in its impact on economic growth in manufacturing industries”.

Analysis

These sentences are where you bring together the theory and contemporary to build up your argument. Remember, the theory should be the focus, and contemporary a bonus. Try and weave a “story” into your analysis if you can — you should be showing the marker how everything fits together, how causes lead to effects, and ultimately bringing together relevant economic concepts to answer the question. Feel free to also include graphs here when they help strengthen your argument.

However

Fit in your “however” statements here. For discuss questions, this however section may take up a larger part of the paragraph if you choose to showcase two opposing arguments together.

Link

Link your argument back to your overarching thesis, and answer the question. Following on from your “however” statement, it can often be a good idea to use linking words such as “nevertheless”, “notwithstanding”, or “despite this” to show that taking into account your arguments presented in the “however” statement, the overarching idea for the paragraph still remains.

Conclusion

Like the introduction, your conclusion should not be overly long. Rather, it should briefly restate the arguments made throughout your essay, and bring them all together again to reinforce how these points help answer the question.

7. Graphs

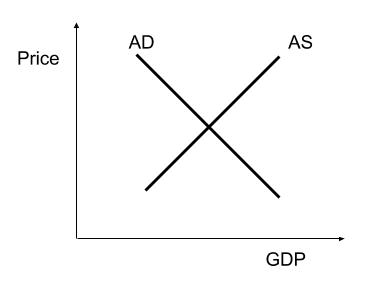

Aggregate Demand / Supply Graph

Graphs are a great way to add extra spice to your essay — not only does it help strengthen your explanations of economic theory, it also makes it look like you wrote more pages than you actually did! Graphs, such as aggregate demand graphs, business cycle graphs, and Phillips curves, can be great in reinforcing your ideas when you mention them in your essay. They usually come either in background paragraphs or body paragraphs, and it’s usually best to draw them about a quarter to a third of the page in size. It’s also good practice to label them as “Figure 1” or “Graph 1”, and refer to them as such in your actual paragraph.

Although they can be beneficial, don’t try and force them either. Not all essays have appropriate graphs, and trying to include as many as you can without regards for their relevance may come across negatively in the eyes of the marker.

8. How to Answer Source Questions

If your essay question involves a source, try and refer to it multiple times throughout your essay. For example, this can be in the background paragraph and two of your body paragraphs. Rather than just adding in an “…as seen in the source” to one of your sentences, try and actively analyse it — show the marker that you understand why they included it, and how it actually helps strengthen your arguments.

9. Plan You Essay

Don’t be afraid to use the first page of your answer booklet as a planning page. Taking a couple minutes before you answer the question to lay out your scaffold for body paragraphs is a great first step to helping ensure that you actually end up answering the question to the best of your abilities. It also serves as a great reminder to keep checking as you finish each paragraph to ensure that you actually wrote what you intended. Just make sure to make it clear to the marker that those scribbles on the page are just a plan, and not your actual essay!

10. How to Prepare for Essays in the Exam

I find it much better to prepare paragraphs and ideas that you can draw upon to help “build up” a response during the exam itself.

Don’t go into the exam with a pre-prepared essay that you are ready to regurgitate — not only are there too many possibilities to prepare for, but it’s also unlikely that you’ll actually answer the question well with a pre-prepared response.

Instead of memorising sets of essays before the exam, I find it much better to prepare paragraphs and ideas that you can draw upon to help “build up” a response during the exam itself. What I mean by this, is that in your mind you have a “bank of different paragraphs” and ideas from all the topics in the syllabus, and when you read the exam, you start drawing from different paragraphs here and there to best formulate a response that answers the question. This allows you to be flexible in answering almost any question they can throw at you.

On top of this, ensure you have a solid foundation in both the theory and contemporary — knowing what statistics or topics to include in your essay is useless knowledge unless you have the actual content to back it up.

Now that you know the basics of how to write a good HSC economics essay, it’s time to start practising! Have a go, try out different styles, and find what works best for you. Good luck!

If you would like to learn from state ranking HSC Economics tutors at Project Academy, we offer a 3 week trial for our courses. Click to learn more!